Should you save more than £1 million in your pension?

Carving out the optimum strategy to save for your retirement, and mitigate tax on your earnings

The removal of the Pension Lifetime Allowance (LTA) charge in 2023 was a significant win for high earners, allowing unrestricted pension growth without an additional tax charge. However, the landscape changed again in October 2024 when it was announced that most unspent pensions will form part of an individual’s estate for Inheritance Tax (IHT) purposes from 6 April 2027.

This raises a crucial question: should you continue maximising pension contributions beyond £1 million, or are there better alternatives? This guide explores the tax benefits and trade-offs of pensions, compared to ISAs and Offshore Bonds.

- What is the right combination of Pensions, ISAs and Offshore Bonds?

- How should your strategy be tailored, depending on your level of income?

- Could you be impacted by these decisions when funding your retirement?

The value of an investment with St. James’s Place will be directly linked to the performance of the funds selected and the value may fall as well as rise. You may get back less than the amount invested.

The levels and bases of taxation, and reliefs from taxation, can change at any time and are generally dependent on individual circumstances.

Save time – receive a no-obligation financial plan, tailored to your circumstances.

Let’s get startedTax considerations for pensions

One of the biggest advantages of pension contributions is tax relief:

- Basic rate taxpayers (20%): Receive 20% tax relief at source, on eligible contributions to a personal pension plan.

- Higher rate taxpayers (40%): Can claim an additional 20% relief via HMRC.

- Additional rate taxpayers (45%): Can claim an additional 25% relief via HMRC.

- On earnings between £100,000 and £125,140, the effective rate of tax relief could be as high as 60% if the pension contributions restore your tapered personal allowance.

Example:

A £10,000 pension contribution effectively costs:

- £8,000 for a basic rate taxpayer.

- £6,000 for a higher rate taxpayer.

- £5,500 for an additional rate taxpayer.

- £4,000 when income between £100,000 and £125,140 is sacrificed to mitigate the tapered personal allowance.

The levels and bases of taxation, and reliefs from taxation, can change at any time. The value of any tax relief depends on individual circumstances.

Tax relief on personal contributions is limited to a maximum of 100% of relevant earnings in the tax year the contributions are paid. Contributions are also limited by the annual allowance. The standard annual allowance is £60,000.

While pensions benefit from tax relief on contributions, withdrawals are subject to income tax:

- 25% of withdrawals are tax-free, up to the Lump Sum Allowance (LSA) of £268,275.

- The remaining 75% is taxed at the individual’s marginal rate (20%, 40%, or 45%).

One rule of thumb is that you ought to save into a pension if, when you retire, your marginal rate of income tax is similar to or lower than when you were working. That would typically result in a strong degree of tax efficiency, given the tax-free element up to the LSA.

However, the tax efficiency of pensions is diminished once the total value of one’s pensions exceeds £1,073,100. That’s because less than 25% of the total value is available as a tax-free withdrawal – for instance, the LSA applied to a pension valued at £3 million is equivalent to only 9% rather than 25%.

The levels and bases of taxation, and reliefs from taxation, can change at any time. The value of any tax relief depends on individual circumstances.

For high earners, the decision to make increased pension contributions may be taken away from you.

Pension tapering regulates the amount high-earning individuals can contribute to their pensions annually while still receiving the full benefits of tax relief.

For the 2025/26 tax year, the standard annual allowance is set at £60,000. Nonetheless, those earning a higher income may see their allowance reduced to as low as £10,000, based on their total yearly income.

Individuals with a ‘threshold income’ over £200,000 and an ‘adjusted income’ over £260,000 are subject to the tapered annual allowance. The reduction in allowance halts when ‘adjusted income’ exceeds £360,000, setting the annual allowance to a minimal £10,000 for pension savings that receive the full benefit of tax relief.

Broadly, ‘Threshold Income’ includes all taxable income received in the tax year, including rental income, bonuses, dividend, and other taxable benefits. From this you deduct any personal pension contributions to personal pension scheme.

‘Adjusted income’ includes all taxable income plus any employer pension contributions and most personal contributions to an occupational pension scheme.

Individuals exceeding both a ‘threshold income’ of £200,000 and ‘adjusted income’ of £260,000 will experience a reduction in their annual allowance by £1 for every £2 exceeding £260,000 in adjusted income.

For instance, an ‘adjusted income’ of £280,000 reduces the annual allowance by £10,000, resulting in a £50,000 allowance instead of £60,000.

The value of an investment with St. James’s Place will be directly linked to the performance of the funds you select and the value can therefore go down as well as up. You may get back less than you invested.

The levels and bases of taxation, and reliefs from taxation, can change at any time. The value of any tax relief depends on individual circumstances.

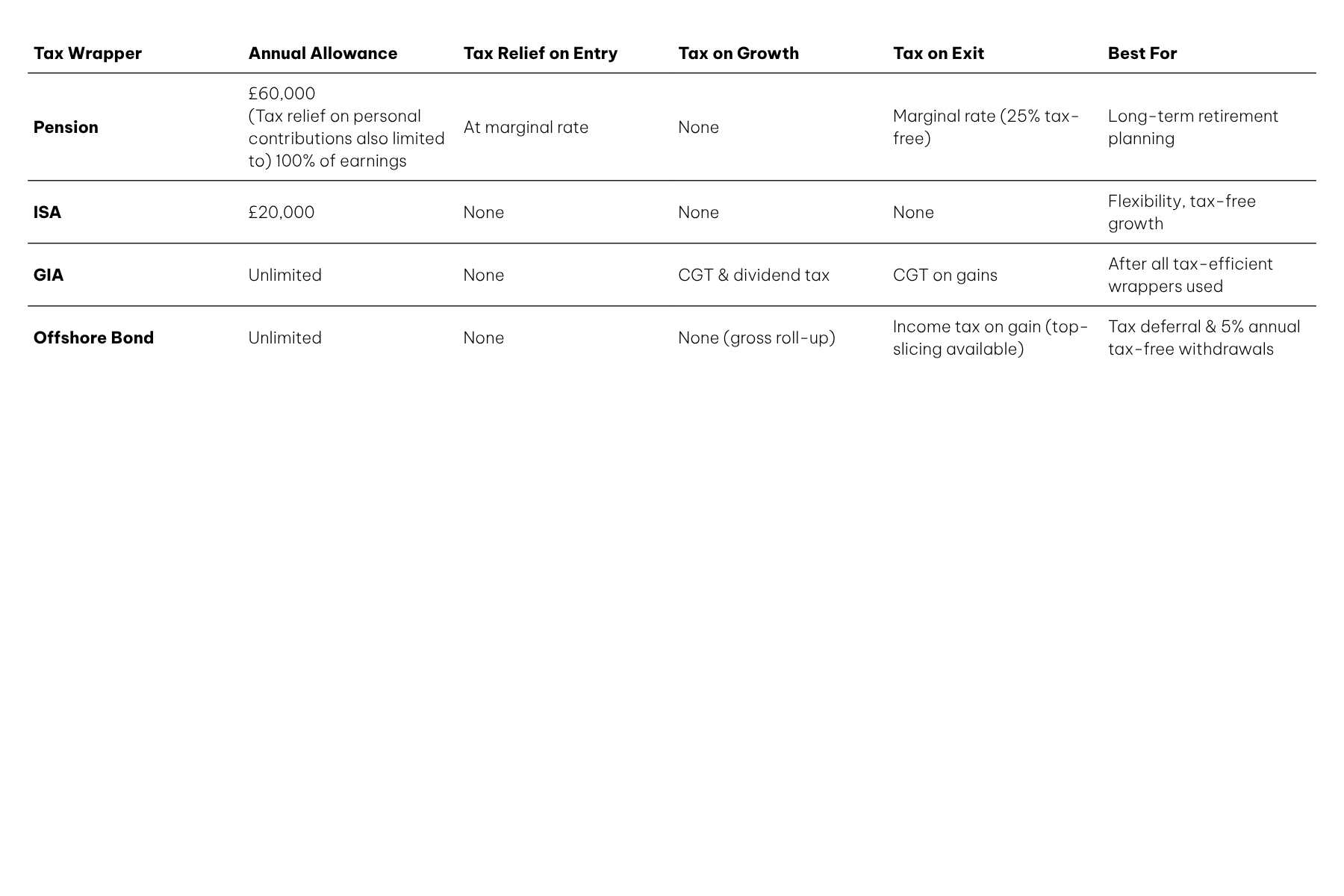

What are the alternatives?

A Stocks and Shares ISA (or Investment ISA) is a tax-efficient way to invest, offering potential for higher growth than a Cash ISA. Any gains or income within an ISA are free from Capital Gains Tax and Income Tax. You can invest up to £20,000 per tax year (6 April – 5 April), and if you’re married, you might consider using your spouse’s allowance to maximise tax efficiency.

While you can withdraw funds anytime, Stocks and Shares ISAs are best suited for mid- to long-term investing, helping you ride out market fluctuations. While you won’t receive tax relief on your ISA contributions like you might with a pension, the withdrawals you make are entirely tax-free.

The value of an ISA with St. James’s Place will be directly linked to the performance of the funds selected and may fall as well as rise. You may get back less than you invested. An investment in a Stocks and Shares ISA will not provide the same security of capital associated with a Cash ISA.

The favourable tax treatment of ISAs may not be maintained in the future and is subject to changes in legislation.

Please note that Cash ISAs are not available through Apollo Private Wealth nor St. James’s Place.

A General Investment Account (GIA) can be a useful addition to a retirement strategy, particularly for individuals who have already maximised their pension and ISA allowances. Unlike pensions, GIAs have no contribution limits, and unlike ISAs, they don’t offer tax-efficient growth or withdrawals. However, they provide full flexibility: you can invest as much as you like, access your funds at any time, and choose a wide range of investments.

While investment growth and income within a GIA are subject to capital gains tax (CGT) and dividend tax, you can make use of annual allowances – like the £3,000 CGT exemption and dividend allowance (currently £500) – to manage tax efficiently. In retirement planning, a GIA can complement other wrappers by offering liquidity, investment flexibility, and tax-planning opportunities, especially when used alongside ISAs and pensions to smooth income and reduce overall tax liabilities.

The value of an investment with St. James’s Place will be directly linked to the performance of the funds you select and the value can therefore go down as well as up. You may get back less than you invested.

The levels and bases of taxation, and reliefs from taxation, can change at any time. The value of any tax relief depends on individual circumstances.

An Offshore Bond is a tax-efficient investment vehicle that can be used as an alternative to or alongside a pension for retirement planning. It offers tax-deferred growth, meaning that any gains within the bond are not subject to UK tax while they remain invested. Instead, tax is only due when withdrawals are made, allowing your investments to grow more efficiently over time.

One of the key benefits of an Offshore Bond is its withdrawal flexibility. You can take up to 5% of your original investment each year, tax-deferred for 20 years, which can be particularly useful for supplementing retirement income without an immediate tax liability.

Offshore Bonds also provide estate planning advantages, as they can be structured under a trust to help mitigate Inheritance Tax. Additionally, they offer investment flexibility, giving access to a wide range of funds, including those not typically available within UK-based wrappers.

While pensions offer tax relief on eligible contributions, they come with restrictions on access, along with the Lump Sum Allowance (LSA) and income tax on withdrawals. An Offshore Bond, by contrast, provides greater control over when and how you draw your money, making it a valuable complement to retirement planning. However, tax treatment will depend on individual circumstances and may change, so professional advice is essential.

The value of an investment with St. James’s Place will be directly linked to the performance of the funds you select and the value can therefore go down as well as up. You may get back less than you invested.

The levels and bases of taxation, and reliefs from taxation, can change at any time. The value of any tax relief depends on individual circumstances.

Next steps

For many, pensions will still be a core part of retirement planning due to the up-front tax relief. However, it may be time to consider diversifying into ISAs, Offshore Bonds, and other tax-efficient vehicles. The right approach depends on income level, retirement goals, and intergenerational wealth planning objectives.

Speak to an expert Private Wealth Adviser to assess your specific situation and develop a tailored strategy that maximises tax efficiency and protects your wealth for future generations.

The value of an investment with St. James’s Place will be directly linked to the performance of the funds you select and the value can therefore go down as well as up. You may get back less than you invested.

The levels and bases of taxation, and reliefs from taxation, can change at any time. The value of any tax relief depends on individual circumstances.

SJP Approved 13/06/2025

Start planning now – invest later. Obtain a bespoke financial plan, tailored to your unique objectives.

Book A Conversation